New objects sighted as Flight 370 search shifts dramatically

New objects sighted as Flight 370 search shifts dramatically

March 28, 2014 -- Updated 1206 GMT (2006 HKT)

Big shift in search for missing plane

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

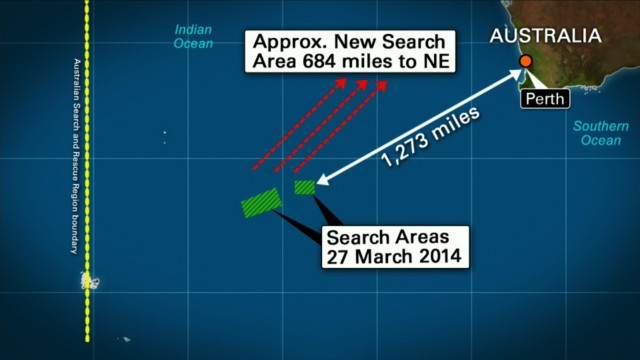

- Searchers abandon search area, shift hundreds of miles to the northeast

- Data suggests the plane used more fuel and crashed farther north, authorities say

- New Zealand plane spots objects, heads back to base for analysis, Australians say

- The search for Flight 370 has gone on for three weeks

In a stunning turn,

Australian authorities announced Friday that they were abandoning the

remote patch of Indian Ocean where search crews had spent more than a

week looking for the plane. A new analysis of satellite data showed the

plane could not have flown that far south, they said.

"We have moved on from

those search areas," said John Young, general manager of emergency

response for the Australian maritime authority.

The new zone is 680 miles (about 1,100 kilometers) to the northeast, closer to the Australian coast.

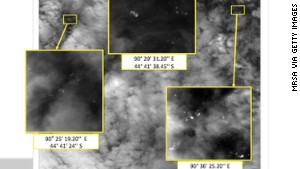

A New Zealand air force

surveillance plane flying over the new search area spotted unidentified

objects floating in the water and was returning to its base in Perth,

Australia, the Australian Maritime Safety Authority said on Twitter.

Photos: The search for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370

Photos: The search for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370

MH370 search area shifts 680 miles

MH370 search area shifts 680 miles

Ex-Malaysian Air CEO defends MH370 pilot

Ex-Malaysian Air CEO defends MH370 pilot

The agency was waiting

for images of the objects for analysis but said the finds would not be

confirmed until Saturday, when a ship is expected to arrive at the site.

Exactly what the plane

had found was unclear, but if the finds turn out to be something other

than plane debris, it would not be the first time.

A Chinese aircraft reported spotting possible aircraft debris early in the search, but that sighting turned out to be nothing.

'We have not seen any debris'

Friday's developments

cap three weeks of frequent false leads in the search for the plane,

which disappeared on March 8 with 239 people aboard.

Malaysian authorities

announced Monday that an analysis of satellite signals sent by the plane

indicated that it must have gone down in the southern Indian Ocean.

Analysts who relied on sophisticated mathematics to come to their

conclusion couldn't offer a specific impact spot, however.

The decision to move the

search zone came after additional analysis indicating the plane didn't

fly as far south as previously thought, acting Malaysian Transport

Minister Hishammuddin Hussein said Friday.

Young said Australian

authorities had concluded a series of satellite images taken over the

old search zone showing objects floating in the ocean did not show

aircraft wreckage.

"In regards to the old

areas, we have not seen any debris," he said, adding that he would not

classify anything satellites or planes have spotted as debris. "That's

just not justifiable from what we have seen."

Hishammuddin seemed to

dispute Young's account, suggesting that the new search area "could

still be consistent" with the idea that materials spotted in recent

satellite photos over the previous search area are connected to the

plane. The materials could have drifted in ocean currents, he said.

Better conditions

The new zone remains

vast -- roughly 123,000 square miles (319,000 square kilometers). It is

still also remote -- 1,150 miles (1,850 kilometers) west of Perth.

Investigators zero in on MH370 captain

Investigators zero in on MH370 captain

Missing Malaysia flight stirs old memories

Missing Malaysia flight stirs old memories

Satellite images show possible debris

Satellite images show possible debris

But Young said

conditions there are "likely to be better more often" than they were in

the old search area, where poor weather has grounded flights two days

this week.

Planes will be able to spend more time in the air because the new search zone is closer to land, Young said.

U.S. flight crews

involved in the search aren't frustrated or disillusioned by the sudden

change in the search, said Cmdr. William Marks of the Navy's U.S. 7th

Fleet.

"For the pilots and the air crews, this is what they train for," he said. "They understand it."

Wasted time?

Some analysts raised their eyebrows at the sudden shift.

"Really? That much debris and we're not going to have a look at it to see what that stuff might be?" said David Gallo of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, who helped lead the search for the flight recorders from Air France Flight 447, which crashed into the Atlantic Ocean in 2009.

Others lamented the amount of time, money and resources that were spent in the old search area.

"This is time that has been wasted, there's no question," said CNN aviation analyst Miles O'Brien.

But Young and Hishammuddin disputed that suggestion.

"I don't think we would've done anything different from what we have done," Hishammuddin said.

Young said previous searches were based on the information authorities "had at the time."

"That's nothing unusual for search and rescue operations," he said.

CNN safety analyst David Soucie said it was "a good sign" that experts had adjusted their assumptions.

"Assumptions are the key

to all of this," he said. "If you assume something and you end up with a

final conclusion, you have to constantly review that."

Vast, evolving search

Expert: 'The ocean is a plastic soup'

Expert: 'The ocean is a plastic soup'

Conflicting reports on pilot's role

Conflicting reports on pilot's role

Partner: My world is upside down

Partner: My world is upside down

The shifting hunt for Flight 370 has spanned oceans and continents.

It started in the South China Sea between Malaysia and Vietnam, where the plane lost contact with air traffic controllers.

After authorities

learned radar data suggested the plane had turned west across the Malay

Peninsula after losing contact, they expanded the search into the Strait

of Malacca.

When those efforts proved fruitless, the search spread north into the Andaman Sea and northern Indian Ocean.

It then ballooned

dramatically after Malaysia announced on March 15 that satellite data

suggested the plane's last position was somewhere along two huge arcs,

one stretching northwest into the Asian landmass, the other southwest

into the Indian Ocean.

The search area at that point reached nearly 3 million square miles.

On Monday, Malaysian

Prime Minister Najib Razak said that further analysis of satellite data

had led authorities to conclude that the plane went down in the southern

Indian Ocean, far from land.

Malaysian officials told

the families of those on board that nobody would have survived. But

many relatives have said that only the discovery of wreckage from the

plane will convince them of the fate of their loved ones.

CNN's Brian Walker and Ben Brumfield contributed to this report.

Comments